the game is sold… AND told

aks about me, aks about me

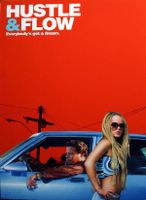

There’s a scene in ‘Hustle & Flow’ when ‘snow bunny’ Nola claps back (verbally) at her pimp D-Jay when she knows he’s trying to get her to agree with him. She reveals that she always knows he’s getting into her head but, because of D-Jay’s manipulation of her in the previous scene, she’s not letting it happen ‘right now.’ She’s not in the mood.

Her stance reinforces the cliché/myth that a pro needs a pimp for mental guidance rather than ass-whippings. Even later in the film after D-Jay is no longer able to ‘guide’ her directly, Nola’s effort to fulfill his last request becomes her ‘mission.’ It is her most successful and, perhaps, satisfying ‘mission’ portrayed in the narrative. (The mission gains new humor in light of the recent payola scandal). D-Jay reinforces the cliché/myth that a pimp is more effective controlling his prostitutes through mental, rather than physical, manipulation. It is difficult to tell if he is a ‘special’ pimp (analogous to the ‘hooker with a heart of gold’ type found in many movies) or if he is typical. Interaction with another person in his ‘trade’ would have clarified for a viewer D-Jay’s professional character a bit more. The glory of his profession is, significantly, absent but the desire to do better… to express something… possibly something ‘true’… is transcendent of his profession.

Of course this conveyance of ‘the truth’ gets complicated when the role-playing piles up quickly. A viewer realizes Terrence Howard is playing a southern pimp (a character built on interviews with southern pimps) trying to portray himself as a rapper. The three songs by D-Jay were created either by Al Kapone or Three-6 Mafia’s DJ Paul and Juicy J. The ‘true’ content helps sell the ‘reality’ of the rap but the flows are arguably as important and it is hard to know how much influence the Tennessee legends had on D-Jay’s/Howard’s authentic spit. Just because the stories are enticing, the delivery often closes the deal. The right combo of articulation and drawl can make any story sound intriguing to particular Yankee ears but delivery with heart is still necessary and D-Jay / Howard comes through… from an embarrassingly comic delivery in Key’s kitchen to the invigorating autobiography on the title song ‘Hustle & Flow (It Ain’t Over)’. And the question becomes: Would Terrence Howard be a better or worse rapper than D-Jay?

D-Jay assumes his ability to pimp can easily translate to selling Skinny Black on a demo. A similar analogy has run through many of the hustler-turned-rapper accounts. The scene between D-Jay and Skinny Black is a quiet but tense battle of wills touching on class war, hustler rivalry and, at it’s most basic, turf. But it is a wonder to watch D-Jay get in the zone and, as he says, find his‘mode.’ His Trojan horse infiltration of Skinny’s ego presents the gauntlet, not ‘thrown down’ but as a velvet glove. D-Jay hooks Skinny Black with the phrase “We miss you, mayn…” D-Jay simultaneously reaches out with open arms and serves a backhand (pimp slap?) to Skinny’s integrity. But as the scene progresses a viewer must ask a Mamet-like question: Who is the most adept at the confidence game, the man asking for a stranger’s confidence… or the stranger giving it? It is in this scene that a viewer might appreciate the complex layering of roles that Ludacris is performing. He was a radio personality from Atlanta who turned into a rapper and is now convincing as an actor portraying a former Memphis local turned rapper trying to regain his image as a Memphis local.

The movie is built on scenes of transaction (the hustle)interrupted by expression (the flow), although it blurs ‘the art of selling’ with ‘the selling of art.’ And although the film conveys a visceral excitement in the recording process it does not shy away from the step-by-step negotiations a recording team must make in that process.

After D-Jay makes hook ups with marijuana as both buyer and seller he finds himself with a keyboard, a potential meeting with a music industry insider and an encounter with a talented but stalled out music producer, Key. Convincing Key to take a chance on his work is almost easier than convincing himself. Many professional studio men will surely smile when Key tells D-Jay to lay the track first and smoke later. Pregnant Shug learns how to sing (or ‘sell’) a hook through vocal tricks (‘hooker’ and tricks!) with the help of a gentle ‘whoop’ to her backside from her pimp and a catchy melody from the unlikely vocal-coach found in a local white boy. Key alters the art for the mart by replacing a clearly offensive hook “Beat that bitch!” to the sexually ambiguous empowerment’ anthem “Whoop that trick!” but we quickly realize it actually works better sonically and, thus, works better artistically.

As the transactions take place between characters, the scenes play out between actors, and the artists negotiate with the audience, a viewer realizes that it isn’t a matter of truth portrayed in art. It is more a matter of an artist being skilled enough to convince the audience to let that artist ‘get in their head,’ to paraphrase Nola in the film.

I don’t know if the pimp lifestyle really can’t provide air conditioning, or if the Memphis accent is portrayed accurately, or if the director has successfully captured the Memphis ‘home-laboratories,’ but in the ‘Memphis’ the characters inhabit, these things become believable. I think most people would find it hard to believe a film about a pimp struggling to become a rapper could inspire a sympathetic view. But when writer/director Craig Brewer and actor Terrence Howard are teamed with musicians like Juicy J that disbelief can be easily suspended. You will see artists in their ‘mode’ and even though you know the hustle is on… you can’t help but fall for it. You just needed the proper guidance.

Microphone Skit feat. D-Jay & Pawn Shop Owner

Whoop That Trick – D-Jay (written and produced by Al Kapone)

<< Home